First the good news: We’re living longer, healthier lives than ever before.

We’re already so used to the idea of greater longevity, in fact, that it may seem ho-hum to learn that boys and girls born in 2008 in the United States have life expectancies of 75 and 81, respectively.

Those life spans, however, represent a bonus of about three decades, compared with Americans born in 1900, according to a report last year from the Census Bureau. And, by the way, Spain, Greece and Austria fared even better, proportionally: Life expectancies in those countries doubled over the course of the 20th century.

Now for the bad news: At this rate, we can’t afford to live so long.

And by “we,” I don’t just mean you, me and our often insufficient long-term-care insurance policies. I mean “we the people.” I mean the bureaucratic “we.”

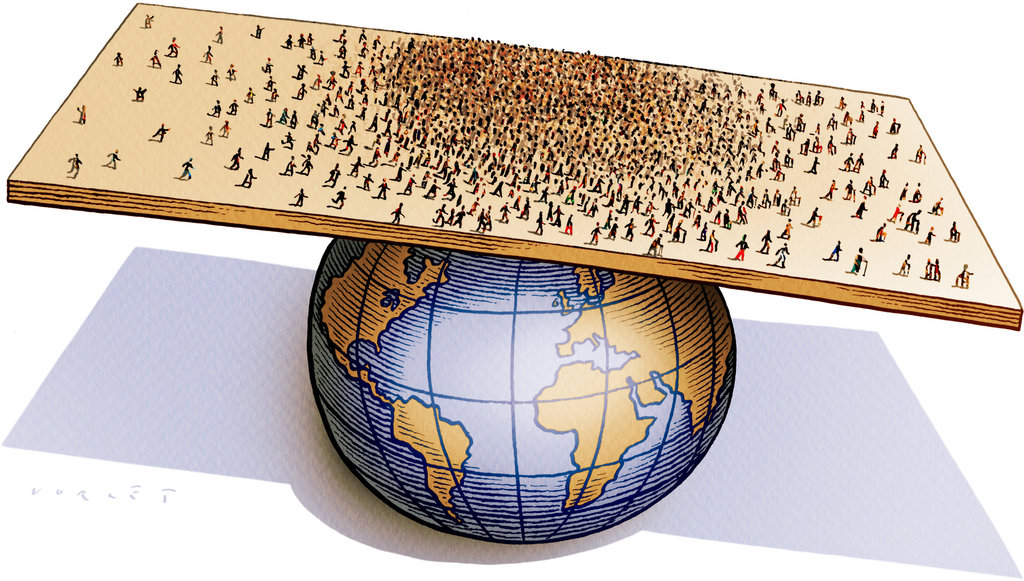

For the first time in human history, people aged 65 and over are about to outnumber children under 5. In many countries, older people entitled to government-funded pensions, health services and long-term care will soon outnumber the work force whose taxes help finance those benefits. This demographic shift also means that the number of people living with dementia, whose treatment is estimated to cost $604 billion worldwide this year, is expected to more than triple, to 115 million, by 2050, according to a report this year by Alzheimer’s Disease International, a group representing 73 Alzheimer’s associations around the world.

No other force is as likely to shape the future of national economic health, public finances and national policies, according to a new analysis on global aging from Standard & Poor’s, as the “irreversible rate at which the population is growing older.”

How are the most developed countries handling preparations for the boom in the elderly population — and for the budget-busting expenditures that are sure to follow?

For a majority, not very well.

Unless governments enact sweeping changes to age-related public spending, sovereign debt could become unsustainable, rivaling levels seen during cataclysms like the Great Depression and World War II, according to the S.& P. report.

If the status quo continues, the report projects, the median government debt in the most advanced economies could soar to 329 percent of gross domestic product by 2050. By contrast, Britain’s debt represented only 252 percent of G.D.P. in 1946, in the aftermath of World War II, the report said.

So what is to be done?

For starters, governments should extend the retirement age, says Marko Mrsnik, the associate director of sovereign ratings in Europe for S.& P. and the lead author of the report. Another no-brainer, he says, is that governments should balance their budgets.

Alas, private citizens often don’t see the logic in curbing public benefits in order to maintain national solvency. Witness France last week, where more than one million people took to the streets to protest pension reform that would raise the minimum legal retirement age to 62 from 60.

Moreover, global aging experts say, measures like pension reform are inadequate, piecemeal responses to the giant demographic shift that is upon us.

If the cost of maintaining aging populations could lead to World War II-era levels of government debt, a solution to the crisis will require a mass-scale collaborative response akin to the Manhattan Project or the space race, says Michael W. Hodin, who is an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and researches aging issues.

Governments, industry and international agencies, he says, will have to work together to transform the very structure of society, by creating jobs and education programs for people in their 60s and 70s — the hypothetical new middle age — and by tackling diseases like Alzheimer’s whose likelihood increases as people age.

“What we need is a very fundamental and profound transformation that is proportionate to the social shifts that are upon us and that is truly innovative in the public arena, innovation that is driven by industry,” says Mr. Hodin.

Here’s one simple suggestion: Influential international organizations, government agencies, companies and academic institutions should take up aging as a cause, the way they have already done for the environment. Although the United Nations, for example, set eight “millennium development goals” — ensuring environmental sustainability, promoting gender equality, and so on — for 2015, the list did not include ensuring the sustainability and equality of aging populations.

“This is quite unacceptable that aging hasn’t been included in these goals,” says Baroness Greengross, a member of the House of Lords in Britain and chief executive of the International Longevity Centre U.K in London.

Here’s another suggestion: Governments with national health programs or other state coverage could start curbing the growth in medical spending ahead of the looming elderquake.

If countries wait to act, says Peter S. Heller, a senior adjunct professor of economics at Johns Hopkins University, they will have to scramble reactively to cut their budgets in response to burgeoning older populations, the way Greece, Ireland and Spain have done recently. At the same time, he says, politicians must also start educating citizens to understand that greater longevity may entail personal sacrifices, like increased savings and a willingness to pay higher shares of their medical and long-term care costs.

But the carrot may be a better approach than the stick, says Laura L. Carstensen, a professor of psychology at Stanford and the director of the Stanford Center on Longevity. She describes her outfit as a multidisciplinary research center whose “modest aim is to change the course of human aging.”

Rather than uniformly extending the retirement age, she says, governments and the private sector could develop incentives that motivate older people to remain in the work force. Those incentives might include bonuses for people who work until they are 70, exempting employers from paying Social Security taxes for employees over retirement age, more flexible work schedules, telecommuting options, and sabbaticals for education and training.

“Maybe culture needs to change first,” says Professor Carstensen, “and policy will follow.”

Finally, some governments and companies may need attitude adjustments so they can view aging populations not as debt loads but as valuable wells of expertise.

“I rather dispute your calling it a problem,” said Lady Greengross when I called to ask her how governments could better handle global aging. “It’s a celebration.”

As one example of how to embrace aging populations, she cites an equality act, recently passed by British legislators, that prohibits discrimination against older people (among others) seeking goods and services like car rentals or mortgages. Separately, she says, Britain next year will eliminate its default retirement age of 65, allowing people to remain in the work force longer.

“In the long run, I’d like to see age irrelevance,” Lady Greengross says, “where people aren’t just labeled by their birthdays.”

Source: The New York Times

Global Coalition On

Global Coalition On